January 29, 2025

4 min read

Which Foods Are the Most Ultraprocessed? New System Ranks Them

Scientists have created a ranking of grocery store items based on their degree of processing

Most grocery stores seem to offer endless options in their aisles, which are full of cereals, pastas and baked goods available in hundreds of shapes and flavors. But a closer look at the ingredient lists of these foods shows that for some of them, there’s not much choice at all. A new study has found that most of the products on our grocery shelves have one thing in common: they’re highly processed.

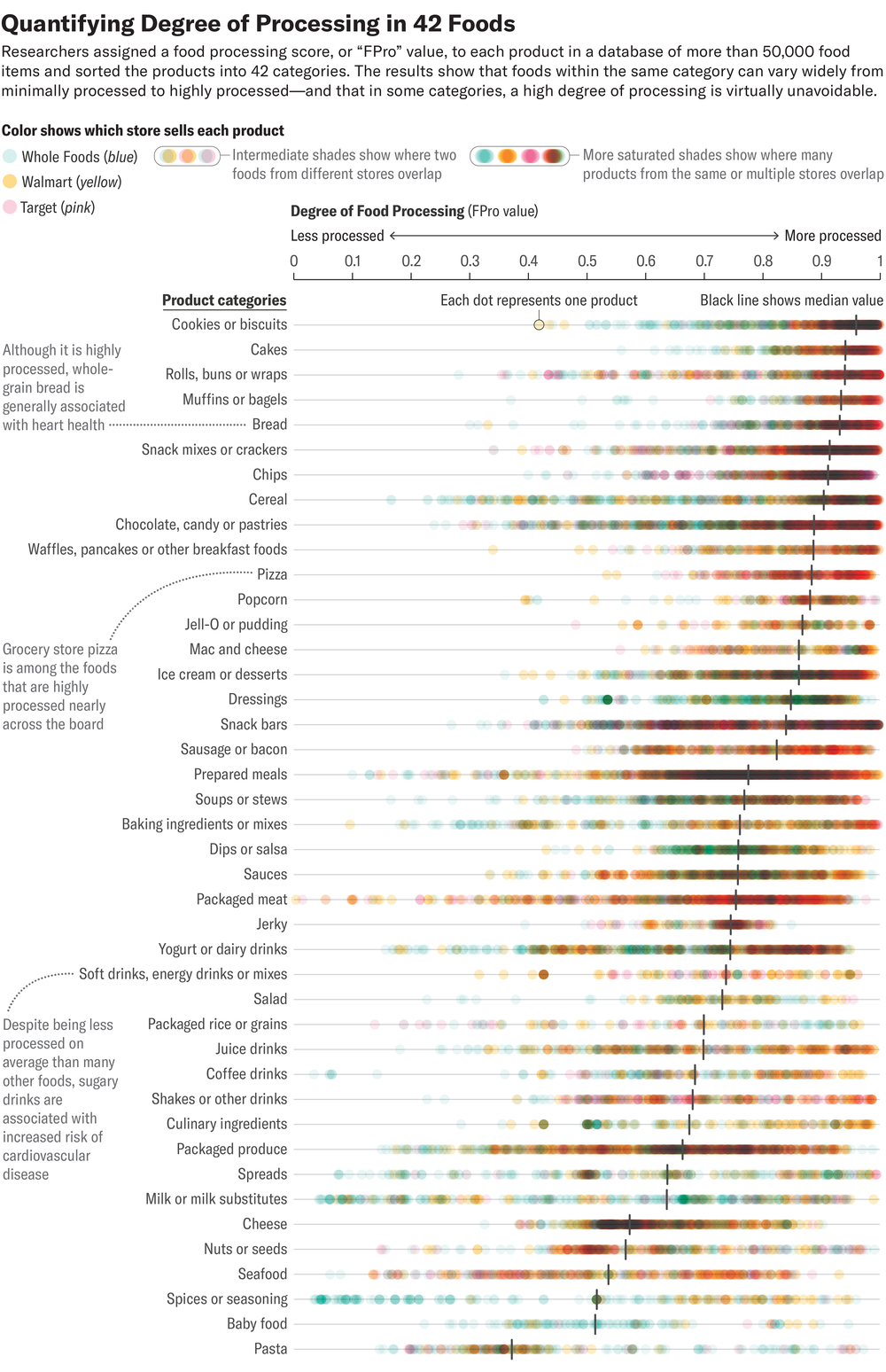

Grocery stores, not fast-food outlets or convenience stores, are the primary source of ultraprocessed foods in U.S. diets. Such foods are made using industrial processes and ingredients that aren’t found at home. To measure just how prevalent these foods are on shelves, researchers used a machine-learning algorithm to analyze more than 50,000 items at three major stores that sell groceries in the U.S.: Whole Foods, Walmart and Target. The results, published on January 13 in Nature Food, revealed that highly processed options dominated the inventory at all three retailers. But Walmart and Target stocked a higher proportion compared with Whole Foods, which offered a slightly greater variety of minimally processed choices.

Having a wide array of brands on the shelves gives shoppers the “illusion of choice,” says study co-author Giulia Menichetti, a statistical and computational physicist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Despite the variety of packaging, most ultraprocessed foods share a common formula: they’re high in sugar, salt, and oil and typically contain additives that enhance their flavor, color and shelf life. Certain industrial processes also alter the texture of the raw ingredients, and this can strip foods of their nutrients.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Diets high in ultraprocessed foods have been linked to poor health, including a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and heart disease. But not all of these foods are equally bad for you. A 2024 study by researchers at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health found that diets high in sugary drinks and processed meats were associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease than diets low in these foods, but the opposite was true for breads, cereals, yogurts and dairy desserts. While these foods can be part of a healthy diet, the new findings show that options within those categories can be limited. Among breads, for example, consumer choices are often dominated by shelf-stable varieties that contain added sugar and other additives instead of whole-wheat bread without additives, a type that is minimally processed.

Blaming the ultraprocessing of foods alone might oversimplify the problem, says Maya Vadiveloo, an associate professor of nutrition at the University of Rhode Island and chair of the American Heart Association’s lifestyle nutrition committee. Diets high in ultraprocessed foods are often dominated by items loaded with saturated fats, salt and added sugar, Vadiveloo says, which suggests some harm might come from poor nutrient balance rather than processing alone. But some research suggests that overconsumption of ultraprocessed foods—which often lack protein and are designed to be easy to eat and highly palatable—can lead to weight gain, too.

While researchers learn more about the specific harms of ultraprocessed foods, the challenge for consumers lies in the limited alternatives available. In some food categories, consumers face little to no real choice, according to the new findings. Certain products—such as chips, bread and pizza—were almost universally ultraprocessed across the three stores. By contrast, other categories such as cereals, milk and snack bars offered more options that ranged from minimally processed to highly processed.

But the choices depend on where you shop. The cereals at Whole Foods, for example, had a wider range of processing and contained relatively less sugar and fewer flavor additives compared with the other two chains’ cereals, which were far more likely to contain corn syrup.

Affordability complicates the picture. Generally, as the level of processing increased, the price per calorie decreased—a trend that was most pronounced in soups, cakes, macaroni and cheese, and ice cream. On average, ultraprocessed foods cost about half as much as their minimally processed counterparts, a practice that reinforces nutritional inequalities, Menichetti says. “This is hitting a specific segment of the population,” she says.

The real proportion of ultraprocessed foods on our shelves could be much, much higher than has been reported, says Barry Popkin, a distinguished professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study. He says the authors used a “guesstimate” of what foods counted as ultraprocessed, as well as “a sample representing about an eighth of the unique packaged foods in the U.S.”

The new scoring system marks a shift from the widely used NOVA classification, which defines ultraprocessed foods as those containing additives or industrial ingredients. The authors’ system, called FPro, goes a step further. It estimates the degree of processing by analyzing a food’s nutrient profile—in other words, it recognizes that “processed” foods exist along a spectrum. The team is now refining the model to predict the specific industrial processes a food undergoes before reaching shelves.

Beyond the complexities of scoring processed foods, Popkin offers a simple rule of thumb: shop for items around a store’s perimeter as much as your budget allows—“the produce, the fish, the dairy,” he suggests. And while a processing score might distinguish between similar-looking items, less processed doesn’t necessarily mean healthy, either. A cookie is still a cookie, Vadiveloo says, no matter how processed it is.