Sam’s father sat slumped on the leather couch in our clinical interview room, head in his hands. He had just finished telling us the long, painstaking history of his son’s descent into psychosis. Sam (name changed to protect confidentiality), then 17, had started casually using marijuana with friends in the ninth grade. He “dabbled” with other substances as well (Xanax, ecstasy), but cannabis was the most consistent.

Sam’s father told me that he and his wife had used cannabis themselves a fair amount in college, and were inclined to agree with their son when he told them, “Don’t worry, it’s just pot!” They pleaded with him to buy it from cannabis shops, rather than getting it “on the street.”

In California, where I work as researcher and clinician studying the links between cannabis use and psychosis, it is not difficult to get a medical marijuana card, even for a teenager.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Sam started high school as a fairly good student with several friends. Over time, he began using cannabis daily. He took it a variety of ways, first with friends at parties, and then increasingly alone. His parents noticed increasingly odd behavior: He covered up the camera on his laptop and then placed cardboard over the windows in his room. He stopped showering. They occasionally heard him mumbling to himself in his room, and he began refusing to go to school. Against his will, his parents took him to a rehab facility for teens. During the three-week program he was fully abstinent from cannabis, but disturbingly his psychotic symptoms got worse rather than better; simply stopping wasn’t enough for Sam to recover.

By the time his family came to our clinic, he had had persistent delusions for more than six months. Sam was fully convinced that the government was following him and constantly surveilling him. It took hours for his parents to convince him to get in the car that day. While we don’t know if cannabis caused Sam’s psychosis, it was striking that his symptoms didn’t go away when he stopped using. It’s possible cannabis had altered his brain chemistry.

What people need to know is that cannabis is simply not the same as the original plant used in the 1960s through 1980s, and even as recently as 10 years ago. These new strains of cannabis are highly potent, making them more addictive and potentially more dangerous, and we are still trying to understand what it does to developing adolescent brains. As a scientist and a parent, I recommend that adolescents avoid using cannabis until at least their mid-20s, but I realize that this may not be the most realistic advice. If your teens are going to use today’s cannabis, it is critically important that you be aware of the data that show what a different beast this substance has become and the risk of major mental health issues.

All cannabis products contain a mix of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the intoxicating component of the cannabis plant, and cannabidiol (CBD), which may have anxiety-reducing properties. In the 1990s the marijuana in a typical joint contained about 5 percent THC.

But genetic modification has drastically increased THC potency; from 1995 to 2015 there has been a 212 percent increase in its content in the average cannabis plant, And it’s not just joints or pot brownies; with the legalization and commercialization of cannabis, there are few limits on the levels of THC for products like fast-acting vape pens and edibles. What teens like Sam can buy today is nothing like what his parents used in college.

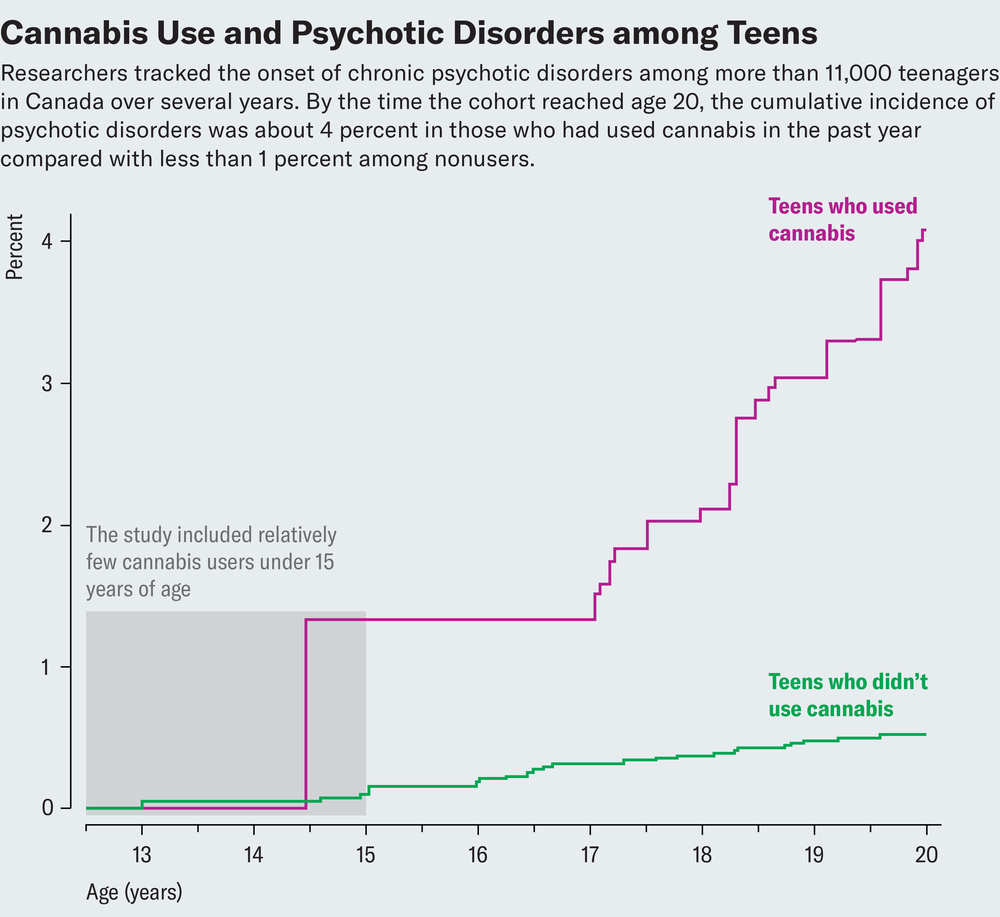

The risk of psychosis rises with the higher potency of THC, the earlier one starts using, and more frequent use. A Canadian research team studying over 11,000 teens found that for cannabis users, there was an 11-fold increase in the risk of developing a psychotic disorder compared with nonusers. In light of such daunting data, some researchers have begun sounding the alarm. But we are struggling to get this information to the people who most need to hear it: parents, educators and legislators.

And while there isn’t a clear consensus that cannabis causes psychosis, studies like the ones I mention, which are well-designed and carefully analyzed, still indicate that the two things are associated.

Another big question we are trying to answer: Why is the increased risk of psychosis so profound in teens? The researchers in my field think it has something to do with the profound rewiring that happens in adolescent brains, which continues into our early 20s. That’s when psychotic disorders typically start. The same molecules in our brains that interact with THC (known as the endocannabinoid system) play an essential role in brain development. And there is growing evidence from both animal and human studies that early cannabis exposure can disrupt the way brain cells, or neurons, respond to what we experience, and how they talk to each other to make those experiences memories.

So how do you talk to your kids about today’s cannabis? When families come to our clinic for youth at risk for psychosis, we ask the kids about why they use cannabis, what their reasons are and how feel afterward. We ask them why they might stop using, and whether they could stop if they needed to. And then: Why not try stopping for a few days and see how you feel? The answers help us assess whether that teen has a cannabis addiction.

Some teens tell us they can stop. But others aren’t willing. For them we take a “harm reduction” approach. That is, we recommend avoiding high-potency products and that they choose instead products with higher CBD-to-THC ratios.

If you have a teenager at home, or will soon, the odds are that they are going to be exposed to a lot of cannabis in many forms—at school, at parties, all around the neighborhood. It is never too early to have that conversation. Part of this is making sure you have good “cannabis literacy” and encouraging your child to seek out reputable sources of information, rather than believe what they hear from friends or see on social media. The National Institute on Drug Abuse is a good start. It can help to set clear rules and boundaries around cannabis use that you all agree on, and establish what the consequences are for breaking those rules. Parents should encourage clear, nonjudgmental communication about use, and encourage their children to share their questions and concerns.

For Sam, we recommended ongoing psychiatric treatment and family therapy, which the family found to be helpful in navigating challenges with the very different expectations they now had of their son, given that he was living with a chronic psychotic disorder. If your child starts experiencing worrisome symptoms or unusual behaviors—such as isolating themselves from others, talking to themselves, or hearing or seeing things that other people don’t—seek psychological treatment right away. Your family physician or child’s pediatrician can provide a referral to a specialist for an evaluation and treatment.

Like so many things our children are exposed to now, the vastly changed landscape of cannabis products and their availability is an experiment that none of us consented to in an informed way. The best we can do is to try and make our retroactive consent (and that of our kids) as informed as possible.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.